Foreword

The Naturalist’s Corner has been in print since 1994 when I began the weekly outdoors column for Scott McLeod, then editor at Waynesville North Carolina’s Enterprise Mountaineer. When Scott left the Enterprise Mountaineer in 1999 to start his own regional weekly newspaper, Smoky Mountain News, the Naturalist’s Corner went too.

I am indebted to Scott and Smoky Mountain News for giving me free rein with the Naturalist’s Corner. The column is not your typical “hooks and bullets” fare. It is, rather, a window on the natural world that opens from the perspective that nature is not something separate from us and that we are inextricably linked to the web of life. A perspective that resonates from Thomas Berry, “The universe is a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects.” And from Chief Seattle, “Man did not weave the web of life; he is merely a strand in it. Whatsoever he does to the web he does to himself.”

I believe the natural world, its mysteries and its marvels, is accessible. Sure there are exotic faraway places like Mount Kilimanjaro, the Great Barrier Reef, the bottom of the Grand Canyon, etc. But the grey treefrog on the glass next to the front door yesterday morning, giving my daughters a close-up view of those cool suction-toes shows we don’t have to travel halfway around the world to get a taste of nature. It’s as close as your backyard; a vacant lot; a greenway or a park – we just have to be receptive.

Putting a very liberal spin on R.D. Laing’s The Politics of Experience – I believe that we are only moved to protect what we love. What we know about nature is so much less than what we love. And what we love is so much less than what there is. And perhaps if we learn more, we will love more and if we love more we will protect more.

“The Naturalist’s Corner” as a weekly column does not have a particular focus other than some connection to the natural world. It focuses, instead, on current issues, observations and/or experiences. These are generally different each week and could range from national, regional or local environmental issues/concerns to area hikes/field trips or to Cope’s gray treefrogs that show up on my doorstep.

A Year From the Naturalist’s Corner: Volume 1 will follow the same format. It is a collection of 52 columns beginning the first week of January and ending the last week of December. All of the columns appeared in their original form in the Smoky Mountain News. Here, some may or may not have been edited and there may be introductions, anecdotes, etc. added.

The columns have no year associated with them, as “A Year from the Naturalist’s Corner” could be any year. I have gone back through the 13 years “The Naturalist’s Corner” has been published in the Smoky Mountain News and pulled 52 representative columns to create a year from the Naturalist’s Corner.

I hope the reader will find these short “stills” taken through the window of the Naturalist’s Corner as interesting and entertaining to read, as they were to write.

Don Hendershot

Chapter One: January

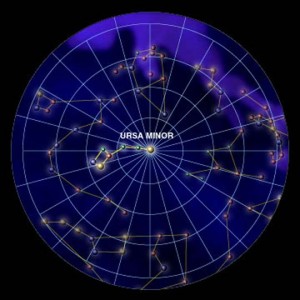

Week One – Little Bear

The Little Bear has made its annual revolution and sleeps once again beneath the North Star. The Little Bear, Ursa Minor, is probably better known as the Little Dipper. For most of December and January the Little Dipper hangs almost directly below Polaris, the North Star.

During the course of the year, the dipper or little bear will swing round the North Star in a counterclockwise motion like a ladle spinning on a hook. By May and June the dipper will be directly above Polaris.

Polaris and Ursa Minor can be located in the northwest evening sky about two fields of vision above the horizon. Because of its fixed position and the fact it never sets, Polaris has historically been important as a tool for navigation.

The Greek name for the star is Cynosure, which means an object of great interest. Polaris is also known as the polestar; the North Star; the Star of the Sea (because of its importance to ancient mariners); Stella Maris and the Lodestar.

Ursa Minor is a relatively new constellation. It was named by the Greek astronomer, Thales, around 600 B.C. One Greek legend asserts Zeus took a fancy to a maiden named Callisto. Hera (Zeus’ wife) in her jealousy turned Callisto into a bear. Zeus, feeling sorry for Callisto, placed the bear in the heavens for all to see. This bear is known as Ursa Major, The Great Bear, or the Big Dipper.

Zeus did not stop there. He also turned Callisto’s son, Arcas, into a bear and placed him in the heavens with his mother. Hera petitioned the powers of the ocean to avenge this slight to her honor. Thus the bears are forced to forever circle Polaris, never having the opportunity to rest beneath the ocean.

To the Southern Paiutes of the western U.S., these two constellations are not bears, but mountain sheep. According to Paiute legend, long ago when the world was young a daring mountain sheep, Na-gah, roamed the earth. Shinoh, Na-gah’s father, was so proud of his courageous son he gave him beautiful earrings (ram’s horns) to make him look important and commanding.

Na-gah was very brave and sure-footed and climbed every mountain he encountered. One day he discovered a massive mountain that reached into the clouds. At first he could not find a trail but after much searching found a cave that first took him downward, then upward to the very peak. As Na-gah climbed inside the dark cave, loose rocks and boulders filled in behind him. When he reached the peak he was trapped with no way down.

Shinoh saw his son at the peak of the tall mountain and saw his predicament. He was sorrowful that his son was destined to die upon the peak. “I will not let my brave son die. I will turn him into a star, and he can stand there and shine where everyone can see him. He shall be a guide mark for all living things on the earth or in the sky.”

Na-gah became Qui-am-I Wintook Poot-see, the Star That Does Not Move, or the North Star. The Big Dipper and Little Dipper are other sheep who have found the mountain and are constantly circling, trying to find a path to Na-gah.

Although Polaris is fixed in the night sky, it has not always been the pole star. As the earth rotates on its axis, it tends to wobble like a gyroscope. So while the tilt of the axis remains nearly constant, the celestial poles trace a circle in the heavens. This wobble is known as precession.

Four thousand years ago the pole star was Thuban, the alpha star of the constellation Draco, the Dragon, which is just below Ursa Minor and Polaris. Today Thuban is about 25 degrees from the celestial north pole.

Polaris is less than one degree from true north. It will be closest to true north in the year 2105. It will remain the “North Star” for centuries. It is the 49th brightest star in the night sky and is about 360 light-years from Earth.

Chapter Five: May

May week 2

Of valleys and lilies

I was leading a program for the Theosophical Society at Lake Junaluska on May 6. We were touring the Corneille Bryan Native Garden when we discovered a striking white lily growing in a wet area. There were a few of these lilies in bloom out in the wet area but we couldn’t find a tag that corresponded. After the program, I looked the lily up in a wildflower guide and found it to be the atamasco or rain lily, Zephyranthes atamasco.

I was unfamiliar with the plant so I did an Internet search to learn more about it. Some of the first hits noted that the atamasco lily was responsible for the place name Cullowhee, which was said to be Cherokee for “valley of the lilies.” Western Carolina University’s staff handbook reinforced this theme: “Although there are several interpretations of the word “Cullowhee,” the most popular is “Valley of the Lilies.” In fact, atamasco lilies did grow in the damp sections of the watershed until the lowlands were drained and turned into farmlands. The lily even appeared as an emblem on the 1940 Catamount annual.”

Curious about the Cherokee – Cullowhee – lily connection, I pursued the thread on more Cherokee oriented sites. That’s when things began to get murky. On a site dedicated to eastern Cherokee place names I found this: “Gula’hi place,” so-called from the unidentified spring plant eaten as a salad by the Cherokee. The name of two or more places in the old Cherokee country; one about Currahee mountain, in Habersham Co., Ga., the other on Cullowhee river, an upper branch of Tuckasegee, in Jackson Co., N.C.”

Another site – Intrigue of the Past: North Carolina’s First Peoples – listed: “Cullowhee: a community in Jackson County; originally named Kullaughee Valley, a Native American name meaning “Place of the Lilies.”

The problem is that almost all the references regarding a Cherokee valley or place of the lilies noted that the area was named for an edible plant, while all the botanical sites I searched were quick to point out that the atamasco lily is highly toxic. I decided to contact plant guru and retired WCU botanist Dan Pittillo to see if he could help me with my quandary.

Pittillo said that when he arrived at WCU he was told Cullowhee was indeed the Cherokee’s “Valley of the Lilies” named for the rare atamasco lily. He said that later, after talking with WCU anthropologist, Dr. Anne Rogers, he wasn’t so sure. So I contacted Dr. Rogers.

In an email Rogers said, “I have asked some Cherokee speakers about the meaning of Cullowhee and these are the answers I got. One thought it might mean “buzzard place”, which is interesting since there is an area behind the campus called Buzzard’s Roost. Another suggested that it was named for nearby Judacullah Rock, and therefore would be translated as “giant place.” ` Yet another person thought it might have come from the Cherokee word meaning “he passed through there”, or something to that effect. I doubt that anyone can give the original meaning today, as the original word was very likely corrupted by English speakers.”

I’m glad I was able to clear that up for you. There is no doubt the word Cullowhee was derived from the Cherokee and there is no doubt the Cherokee knew of a “valley” or “place” of the lilies. But I seriously doubt the Cherokee were dining on atamasco lily salads.

As for the plant itself, like I said before it is quite striking. The flower is on a naked stalk, about a foot high. The bud starts out pink but opens to reveal three sepals and three petals that are satin-white. The petals and sepals fade to pink again after pollination.

The atamasco lily is pretty common across the Piedmont and Coastal Plain of North Carolina and Virginia. It is rare in the mountains. In Wildflowers of North Carolina, the authors note that the plants “are present also in a few western counties.” However the Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas,

Shows them only from Henderson County in the mountains.

Zephyranthes atamasco is also known as the rain lily. Zephyranthes is derived from the Greek “Zephros” – god of the west wind – and “anthos” meaning flower. So it is literally the flower of the west wind. It is believed that this might refer to the winds that bring the spring rains the lily thrives on.

Chapter Eight: August

August week 3

Rankin Bottoms

We first visited Rankin Bottoms in April. We could easily go again – with its backwater gooey mud and swamp creatures Rankin Bottoms is a place I often go when feeling homesick for Louisiana.

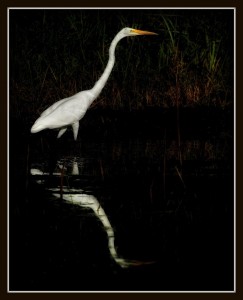

Rankin Bottoms is the closest I’ve been to the Louisiana delta where I grew up in years. The mud is not buckshot but it is slick and black. There are no cypress trees, but willows rise from the water and buttonbush hugs the shore. Carp stand on their heads in the muddy water, their tails waving in the air. Herons and egrets fill the willows and wade in the shallows. Cicadas sing from the treetops in the heat.

I have never seen Rankin Bottoms full of water, but my heart’s eye sees a forest of water beneath the willows like the oxbow lakes along the Mississippi where I used to fish with my Dad as a kid. Douglas Lake is a TVA hydroelectric project and as is the norm, draw down starts in late summer. As the water recedes, mud flats appear. Migrating shorebirds by the thousands take advantage of this man-made stopover and drop in to feed and rest during their long journey south. Terns, gulls, grebes, cormorants and ducks also take advantage of this resting place. There is an osprey nest on an old railroad trestle, and cliff swallows nest beneath the bridge across the French Broad.

I discovered Rankin Bottoms virtually, while I was perusing Jack Siler’s website — a compilation of birding listservs from across the country – looking for a place within driving distance to get a glimpse of migrating shorebirds. The most amazing thing about this muddy slice of my past is, it’s only an hour from Waynesville. Rankin Bottoms is located at the eastern end of Douglas Lake at the French Broad River embayment just outside Newport, TN, off U.S. 25 east.

I remember the first time I visited the bottoms. Bob Olthoff, Sean O’Connell and I went up to check it out. Bob had been there earlier in the week and knew where we were going. We drove down the road towards the old coal tipple along the railroad track. We didn’t quite make it to the tipple as the road disappeared beneath the water.

As we stopped we saw a shorebird in the road. A cursory glimpse revealed a killdeer. But further study through binoculars revealed a different story. It was a ruddy turnstone. If someone had told me that morning that I would find a ruddy turnstone on a gravel road in east Tennessee I probably would have disagreed.

The next trip down was with Bob, Cathy King and Beth Brinson. We had been following Rankin on the listserv and knew the water was falling and that canoes/kayaks provided the best medium for observing shorebirds.

Shorebirds were there in good numbers. We saw hundreds, representing at least 12 species. We also saw large numbers of black terns, one Forster’s tern, two ring-billed gulls and a few black-crowned night herons.

I also got a firsthand comparison between Rankin Bottoms mud and delta buckshot. Bob turned to get a better look at a couple of black terns, the canoe turned, and we got a good look at the bottom of the canoe and a good feel for the mud flat about a foot beneath the surface of the water.

Rankin Bottoms mud looks a little like buckshot and it exudes a nice, damp organic aroma. But it is not buckshot. We were able to stand without much effort. I don’t think we sank much below our ankles. In the Louisiana delta we would have never seen our knees.

I understand that the high water of spring and summer offers great canoeing through the willows with good looks at nesting prothonotary warblers and little green herons. I can hardly wait. I hope Bob has his sea legs by then.