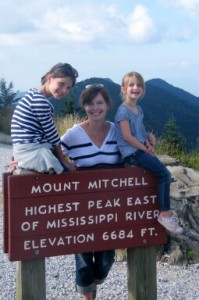

Last week I wrote about the dark subterranean part of our little family adventure, which was a visit to Linville Caverns – see http://www.smokymountainnews.com/outdoors/item/8139-from-the-darkness-to-the-light-%E2%80%93-literally. From the dark caverns of Linville we turned our attention to the light and headed for the highest peak east of the Mississippi – Mt. Mitchell.

Our Linville Caverns guide told us, at the end of the caverns, that we were a half-mile underground. I find that kind of hard to believe – maybe she meant we were a half-mile below the summit of Humpback Mountain. But if we were, indeed, a half-mile underground, our ascent to the top of Mt. Mitchell would have been a total elevational gain of approximately 9,324 feet.

Both of these disparate worlds owe their existence to their geology. The soft shady dolomite of the caverns allows the water to course through creating the various chambers and tunnels. And the hard igneous and metamorphic rock of Mt. Mitchell has allowed it to withstand millions of years of erosion.

Mt. Mitchell is an amazing and beautiful place but it is, regrettably, a shadow of its former self. When Dr. Elisha Mitchell, for whom the peak is named, and French botanist Andre Michaux were exploring Mt. Mitchell back in the early 1800s they documented a robust and diverse Spruce-Fir forest comparable in climate and composition to southern Canada. Fraser fir (named after Scottish botanist John Fraser) dominated the landscape of Mitchell and other peaks at and above 6,000 feet. A little bit lower they were joined by red spruce and below that northern hardwoods, including the majestic American chestnut cloaked the mountainsides.

For millennia those forested peaks withstood snow, ice, wind, drought and occasional wildfire. But they were no match for crosscut saws and/or introduced exotic pests. The slash and burn timbering practices of the late 19th and early 20th centuries decimated those mountaintop forests. And as they were trying to rebound the chestnut blight wiped out the American chestnut and the woolly adelgid laid waste to the Fraser fir. And today’s mountaintops are still under siege from air pollution, acid rain and acid fog.

The timbering practices of that period were so destructive that citizens began to voice concern. That concern spurred North Carolina governor Locke Craig to push for protection of Mt. Mitchell and in 1915 a law passed in the General Assembly creating the North Carolina State Parks System and Mt. Mitchell became the first North Carolina state park.

While today’s forests don’t match their early grandeur they are still pretty amazing and diverse. Yellow birch, fire cherry, mountain ash and mountain maple compete to fill the gaps created by the loss of the firs. Wildflowers like bush honeysuckle, St. John’s wort, gentian, purple-fringed orchid, pink turtlehead, goldenrod and more bloom from spring through fall.

Black bear, the occasional white-tailed deer, bobcat, coyote and gray fox roam the forests along with chipmunks, red squirrels, striped skunks and groundhogs. More than 90 species of birds have been recorded from Mt. Mitchell. And the list includes many high-elevation specialties like hermit and Swainson’s thrushes, pine siskin, red crossbill, winter wren, northern saw-whet owl and golden-crowned kinglets.

Ridge-junction overlook on the Blue Ridge Parkway at the entrance to Mt. Mitchell State Park is an amazing place to watch fall migrants. Migrating passerines (songbirds) stream through the pass there at the base of Mt. Mitchell from late September through October, sometimes in staggering numbers. I have counted as many as 100 ruby-throated hummingbirds in the span of two hours, along with 45 black-throated green warblers and numerous other species.

And if that 90-degree flatland heat starts to suck the life out of you in July and August a quick trip to Mt. Mitchell where the average high temperature for those months is around 66 degrees Fahrenheit can be just what the doctor ordered.